China: Sovereign & Economic Risk Report

- Founder & CEO

- Jun 22, 2025

- 20 min read

Presented by Prostancy Team |

Long-Term Foreign Currency Ratings | ||

A Outlook Stable |  A1 Negative |  A+ Outlook Stable |

Capital City | Beijing | |

Population | 1.416 Billion (2025 Est.) | |

Continent/Region | East Asia | |

GDP (Nominal) | USD 18.6 Trillion | |

National Income Per Capita (Nominal) | USD 13,306 | |

Unemployment Rate (Surveyed Urban, 04/2025) | %5,1 | |

Consumer Inflation (CPI, YoY, 05/2025) | -0.1% |

CDS 5y bps (5 Year Credit Default Swap) 53,24 China's 5-year credit default swap (CDS) premium is 53.24 basis points as of May 26, 2025. CDS premiums fluctuated between 51.76 and 61.69 basis points in May 2025. |

Economic Deep Dive

Strengths

| Weaknesses

|

Economic Strengths & Weaknesses |

Economic Strengths

Massive and Diverse Economy: China's enormous, vibrant economy provides a vast domestic market and significant innovation potential, forming the foundation of its economic position in the world.

Dominant Manufacturing Powerhouse: The country possesses a world-leading industrial base, particularly in high-tech sectors like electric vehicles and green energy, which has propelled it to record trade surpluses and global market dominance.

Strong State Capacity and Policy Control: The government exhibits formidable policy effectiveness, enabling it to mobilize vast resources to meet economic targets, manage crises, and direct industrial strategy, supported by a large domestic savings pool and capital controls that ensure financial stability.

Economic Weaknesses

Structural Demand Imbalance: The economy is characterized by persistently low domestic consumption and an overdependence on government-driven investment and net as key growth drivers, making it extremely susceptible to external demand shocks as well as trade protectionist policies.

Severe Property Sector Crisis: A sharp and persistent downturn in the real estate market, which at one point accounted for up to one-third of economic growth, remains a significant drag on investment, consumer confidence, and local governments' fiscal health.

Escalating Debt Levels: The economy is also weighed down by a significantly higher and increasing debt-to-GDP ratio for all sectors, with specific weaknesses concentrated on the non-transparent liabilities of Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs).

Intensifying Geopolitical Headwinds: An escalating trade and technology war with the United States and growing protectionism from other major trading partners directly imperils China's export-led growth model and is resulting in a sharp slowdown in foreign direct investment.

Macroeconomic & Social Environment Analysis |

This section provides a detailed analysis of China's macroeconomic performance, the policy initiatives taken, and the structural challenges that define its current economic scenario. The assessment reveals an economy at a critical juncture, whereby government-driven growth is running into fundamental imbalances and a challenging external environment.

Economic Growth: A State-Engineered Trajectory

China's economy technically achieved its "around 5%" 2024 GDP growth target on a full-year basis with a 5.0% increase. The performance was helped by a stronger-than-expected fourth quarter, during which year-on-year growth picked up to 5.4%. The government has maintained its 5% 2025 growth target, suggesting a resolve to offer stability amidst growing headwinds. Consensus forecasts among international institutions point to a sharp moderation in the offing. The World Bank predicts growth to slow to 4.5% in 2025 and 4.0% in 2026 amid the negative impacts of global trade restrictions and the chronic local property slump. Moody's is even more bearish, forecasting growth of just 3.8% for 2025, well below the government's official target.

A closer look at the structure of growth in 2024 reveals a significant decline in its quality, reflecting profound structural imbalances. The 5.0% headline rate was not due to domestic, demand-led growth but was predominantly a consequence of government intervention. Growth was supported by two key sources: a record net export contribution of 30% of GDP growth, the largest proportion since 1997, and an increase in state-led expenditure, which contributed 25%. This was needed to counterbalance the steep weakness in domestic consumption, which had a historically low contribution to growth at 45%, as well as a slowdown in the real estate sector. Investment in real estate, once a key driver of economic activity, fell sharply by 10.6% in 2024. The government, in response to this setback, invested resources in upgrading manufacturing investments, which showed a robust growth of 9.2%, particularly in high-end sectors like information technology services, which registered over 10% growth.

This phenomenon reveals that investment is increasingly being utilized as a "residual" tool to satisfy the growth goal set by political mandates. When organic growth stemming from consumption falters, state-owned enterprises and banks are instructed to raise fixed-asset investment to close the gap. This over-reliance on investment and exports, when domestic demand is still at a muted level, forms a risky dependence. It accommodates industrial excess capacity because the economy now produces far more than it can consume domestically, and makes China extremely vulnerable to the mounting trade war and rising protectionism of its principal trading partners. The 5% growth target, therefore, came at the cost of further worsening the structural imbalances and accumulating enormous future financial liabilities, prioritizing short-term stability over long-term economic well-being.

Fiscal and Monetary Policy: All Hands on Deck

Amidst the context of great economic challenges, the Chinese government has implemented a range of supportive policies. On the fiscal policy front, Beijing has taken a more expansionary approach, exceeding its long-held 3% deficit-to-GDP ratio by aiming for a record high target of 4% by 2025. The fiscal stimulus is being channeled through initiatives like the issuance of RMB 1.3 trillion of ultra-long-tenor special treasury bonds, which are aimed at financing major infrastructure projects and strategic programs like nationwide equipment upgrades.

Meanwhile, the People's Bank of China (PBoC) is pursuing a dovish monetary policy, as embodied in a cautious easing trajectory. This involves steps aimed at fostering liquidity in the banking system and nudging lending rates down with the hope of spurring credit demand and offsetting the deflationary pressures bearing down on the economy. The PBoC, however, has moved carefully to steer clear of triggering sharp renminbi depreciation that may set off capital outflows.

The nature of this policy response is revealing. It is much more supply-side focused, with fiscal stimulus aimed at funding infrastructure, manufacturing, and the restructuring of municipal government debt instead of household income and consumption directly. Multilateral institutions such as the World Bank have consistently argued that unleashing consumption is the path to China's sustainable growth, advocating for the creation of more robust social safety nets to lower households' desire for elevated precautionary savings. With its policy mix still favoring production over consumption, Beijing risks deepening the economy's fundamental structural imbalance. This approach will result in a greater supply of industrial overcapacity, hence placing Chinese businesses in the situation of dumping their excess on foreign markets at reduced prices. Such a phenomenon will hence be anticipated to unleash additional protectionism by trading partners, thereby generating a negative feedback process that weakens the export function that the policy aims to enhance.

Debt Profile: The Elephant in the Room

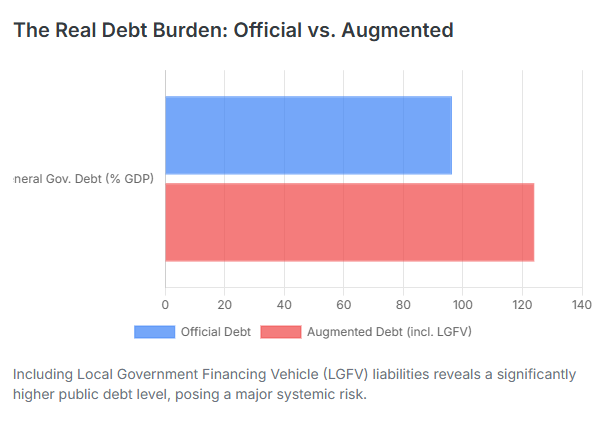

China's indebtedness has taken on alarming dimensions, constituting the greatest long-term threat to its economic stability. Latest estimates indicate that the nation's total non-financial sector debt-to-GDP ratio escalated to 303% as of the period ending 2024, up from 292% as of 2023. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates the general government gross debt to hit 96.3% of GDP in 2025. Nevertheless, this technical estimate fails to represent the actual magnitude of the public debt. Adding the non-transparent borrowing of Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) produces an "augmented" government debt ratio above 124% of GDP, revealing a considerably weaker fiscal position.

By sharp contrast, China's foreign indebtedness is characterized by low levels and safe ratios. The external debt to GDP ratio stood at a low 12.8% at the end of 2024, well below the internationally accepted warning line of 20%. Moreover, the nation's enormous foreign exchange reserves, the world's largest, offer a huge safety net, as short-term foreign debt only represents 42.4% of these reserves.

This dualism emphasizes that the principal danger lies not in an external default but in a domestic debt crisis. The epicenter of this risk is the intertwined vulnerabilities of LGFVs and the property market. The property market has severely cut a key revenue source of local governments, i.e., land sales, and decreased the value of assets possessed by the banking system, which is the primary financier of developers and Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs). A default surge in LGFVs would have systemic implications, which would paralyze the domestic credit system. The standard response of the central government includes debt-swap schemes and other restructuring arrangements that allow the transfer of problematic debts from public local accounts to the sovereign's books. Although this method reduces the near-term risk, it simultaneously nationalizes enormous contingent liabilities, thereby putting severe long-term pressures on public finances and raising the prospects for future sovereign credit rating downgrades.

Inflation and Employment: Signs of Deflationary Strain

China is currently experiencing a protracted spell of very low inflation that is creeping towards the threshold of deflation, pointing to fundamental weaknesses in domestic demand. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) has recorded negative year-on-year readings for four months in a row, with a decline of 0.1% registered in May 2025. The average rate of inflation for all of 2024 was a mere 0.2%, well below the official 3% target. The situation is also worsened at the factory gate, where the Producer Price Index (PPI) continues to drop, reflecting soft industrial demand and overcapacity. The labor market, while appearing healthy on the surface with a headline urban jobless rate of 5.1% in April 2025, conceals severe underlying pressure.

Unemployment among youth, encompassing the age group of 16-24 years, is a concerning factor, standing at a high 15.8%. This highlights a mismatch between the skills that new graduates possess and the needs of the contemporary economy. More troubling, the link between economic growth and job opportunity creation has significantly weakened. The Chinese economy has created fewer than half of the net new job opportunities generated during the previous five-year period over the last five years, even with comparable aggregate GDP growth rates. The employment and inflation trends being seen are generating a self-reinforcing negative feedback loop that is weakening the domestic consumption necessary for economic rebalancing. The ongoing deflation is tempting the consumer to postpone his or her spending in hopes of further price drops, thereby reinforcing the decline in aggregate demand.

It also increases the real cost of debt for households and firms, reducing their ability to spend and invest. At the same time, high youth unemployment reduces the income and confidence of a significant population, resulting in increased precautionary saving and decreased aggregate consumption. This, in effect, compels producers to become increasingly dependent on foreign markets for offloading their output, thereby entrenching the export-led model that is already under pressure from global protectionist policies. The processes of deflation, high indebtedness, and a depressed labor market are all characteristic of the aspects of a "balance sheet recession." It is a time when the private sector focuses more on deleveraging than on spending, thus diminishing the efficacy of conventional monetary policy and putting immense pressure on the government to spend more by debt-financed fiscal stimulus.

Governance & Institutional Assessment |

This section looks at the effectiveness of China's government and its regulatory regime, a key component for determining ongoing political and regulatory risk. Although the nation has a high degree of administrative effectiveness, this is tempered by very low scores on political freedoms and adherence to the rule of law, presenting an unusual and difficult environment for investors.

World Bank Governance Indicators (WGI)

World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) aggregates perceptions of governance quality among broad groups of international stakeholders into a common framework for cross-country comparison. China's 2023 scores, the most recent available year, on the six dimensions paint a profile of contrasts. The state performs well in dimensions related to state capacity but ranks among the world's worst on indicators of political freedom and accountability. To place this in context, the following table contrasts China's percentile rank (100 being the most favorable) with the median of A-rated peer nations.

Governance Indicators (2023 Percentile Rank) | China | A-Rated Peer Median |

Voice and Accountability | 4.7 | 75.2 |

Political Stability & Absence of Violence | 23.8 | 70.5 |

Government Effectiveness | 78.8 | 85.1 |

Regulatory Quality | 45.3 | 82.4 |

Rule of Law | 43.3 | 84.6 |

Control of Corruption | 58.9 | 83.3 |

Institutional Analysis: The Party-State Nexus

The WGI data provides quantitative confirmation of the essential characteristics of China's governance system. The country's high score in Government Effectiveness reflects the significant ability of the party-state to make and implement policy, invest in large endeavors such as infrastructure, and regulate the economy at a macroeconomic level. This level of efficiency is a critical element that has helped China to develop quickly economically.

But it is done at the cost of Voice and Accountability completely, where China's percentile score is in the lowest single digits in the world. The CCP has complete and unfettered dominance of all dimensions of governance. There are no institutional means to facilitate political opposition; the National People's Congress is a rubber-stamp legislative body, and the government strictly controls the media, online discourse, and all avenues of civil society.

The indicators of the Rule of Law and Control of Corruption present moderate scores, necessitating careful interpretation. Although President Xi Jinping's signature anti-corruption drive has been extensive, its application tends to be opaque and is viewed by external analysts as a means of eliminating political opponents and entrenching power. The judiciary is not independent of the CCP, implying that the "rule of law" takes a backseat to the "rule of the Party" in practice. Likewise,

Regulatory Quality is a premier concern for international business. The opaqueness, coupled with political shock risks of abrupt policy shifts—evidenced by recent crackdowns on the technology and private education industries—results in an extremely uncertain and unpredictable business climate.

This governance framework offers investors a fundamental trade-off: the possibility of high short-term execution efficiency when aligned with government objectives, versus exposure to extreme long-term political and regulatory risk. The intense concentration of power in the hands of a single leader, Xi Jinping, has taken this "key person risk" to heights unseen in decades. Policy direction is increasingly attuned to the choices and views of an individual, hence rendering long-term strategic planning by foreign businesses challenging. Such increased political and regulatory uncertainty is a primary catalyst for the recent steep plunge in foreign direct investment, along with the aggressively unfolding "de-risking" approaches pursued by multinational companies.

Banking Sector Stability Review |

China has the largest banking system in the world in terms of assets, which is the main tool used to carry out state policy and circulate the country's economy. Therefore, its stability is a topic of both national and international significance. This sector is presently negotiating a challenging landscape that includes declining credit expansion, constrained profitability, and increased asset quality risks brought on by the real estate crisis.

Sector Overview and Structure

The Chinese banking sector is dominated by state-owned commercial banks (SOCBs). In terms of assets, the Bank of China (BOC), China Construction Bank (CCB), Agricultural Bank of China (ABC), and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) are among the largest financial institutions in both China and the world. Although these banks co-exist with other national and regional lenders and institutions, they are much more than just commercial companies; they are indispensable instruments for the state to guide the sector by providing loans to key sectors, to boost economic growth during recessions, and to ensure financial stability in line with government policies.

Asset Quality and Risk Exposure

The asset quality of the Chinese banking industry is said to be stable. Large commercial banks' reported non-performing loan (NPL) ratio has been low, averaging 1.2%, and has been improving in recent quarters as a result of aggressive write-offs and disposals. International analysts, however, are generally skeptical of the accuracy of these official figures. The non-performing is a more thorough metric.

A more concerning picture is painted by the asset (NPA) ratio, which takes into account special-mention loans, forbearances, and other restructured assets. S&P Global predicts that the economic slowdown, the ongoing real estate crisis, and pressures from the US-China trade war will cause the sector-wide non-performing asset (NPA) ratio to increase to between 6.1% and 6.3% in the 2025–2026 period.

The primary sources of risk are the sector's immense exposures to the troubled real estate sector and highly indebted LGFVs. While the NPL ratio for property development loans appears to have stabilized after a sharp deterioration, it remains at elevated levels, and the risk of further defaults and contagion remains significant. The financial health of LGFVs is directly tied to local government finances and the property market, creating a nexus of risk that is concentrated on bank balance sheets.

Capitalization and Profitability

The Chinese banking industry appears to be well-capitalized. By the end of 2024, the overall Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) was a strong 15.7%, well above the legal minimums established by both national and international standards. The state's implicit and explicit support for this strong capital position is further supported by reports that it has started new rounds of capital replenishment for major banks to guarantee their ability to support the economy.

Profitability is facing extreme and increasingly intense pressure in the face of these high capital buffers. Banks have to choose between competing aggressively for deposits, keeping funding costs high, or policy mandates to cut loan prices to help borrowers. Net interest margins (NIMs) have thereby been massively compressed, and important profitability metrics like return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) have hit historic lows.

This case illustrates a fundamental paradox of the Chinese financial system: it appears well-capitalized and sound, but is operationally a quasi-fiscal institution whose true risk structure is obfuscated by state directions and subsidies. Strong CAR and huge loan-loss provisioning coverage levels suggest strength. However, the emergence of an estimated rise in the NPA ratio to over 6% indicates extraordinary underlying stress, which cannot be inferred from officially reported NPLs. The pressure on profitability arises directly from the policy role of the banks, as they have to give up their margins in pursuit of national economic objectives. The provision of state capital is an unstated acknowledgment of this systemic pressure. System stability does not arise from commercial viability but from the willingness and ability of the sovereign to provide a continuous backstop. Therefore, any estimate of the banking sector's risk cannot be detached from that of the sovereign fiscal health itself. A serious deterioration in public finances would directly call into question the state's capacity to support the banks, potentially unveil the true size of the bad debt within the system, and unleash a financial crisis.

External Sector, Trade, and Geopolitics |

China's economic system is intertwined with the world economy but is undergoing a radical and disputed transformation. Its export-led model of development is clashing with rising protectionism and strategic competition with the United States, leading to a slowdown in foreign investment and forcing a discomfiting economic rebalancing.

Foreign Trade Relations: An Export Juggernaut Facing Headwinds

China's status as a world manufacturing and exporting giant continued in 2024, as the country recorded a record-breaking trade surplus of almost USD 1 trillion based on the power of a 5.9% growth in exports. The growth was driven by its leadership in electromechanical goods, primarily the record global sales of electric vehicles (EVs), solar panels, and lithium-ion batteries, and noting its leadership in green technology production.

China's regional trade is also closely bound up with its partners, with ASEAN now constituting the biggest trading bloc. However, in terms of volume and as a geopolitical tension source, its relationship with the advanced European Union and United States economies remains vital. The latest figures available early in 2025 indicate these underlying relationships.

China's Major Trading Partners (Jan-Feb 2025) | Total Trade (USD Billion) | China Export (USD Billion) | China Import (USD Billion) |

ASEAN | 143.8 | 87.2 | 56.6 |

European Union | 115.9 | 79.0 | 36.9 |

United States | 102.1 | 75.6 | 26.5 |

South Korea | 46.7 | 20.6 | 26.1 |

Hong Kong, China | 45.3 | 43.3 | 2.0 |

Japan | 45.1 | 24.0 | 21.0 |

Taiwan, China | 43.2 | 11.2 | 31.9 |

Trade Relations with Turkey

The bilateral trade relationship between the two nations is characterized by a chronic and high structural imbalance. During 2023, total trade was disproportionately in favor of China, with Chinese exports to Turkey totaling USD 44.6 billion while Turkish exports to China amounted to just USD 3.77 billion, resulting in Turkey having more than USD 40 billion trade deficit. This trend continued up to early 2025, with March figures showing Chinese exports to Turkey standing at USD 3.45 billion and imports at a mere USD 344 million.

The composition reveals the different roles of the two nations in international value chains. China sends technology and high-value-added manufacturing goods to Turkey, with top categories including broadcasting equipment, computers, semiconductors, and automobiles. On the contrary, Turkish imports into China are dominated by raw materials and intermediary products such as marble and other stone, chromium ore, and borates.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): A Worrying Decline

One of the clear signs of an evolving global attitude towards China is the steep decline in foreign direct investment. By balance-of-payments estimates, net inward FDI flows fell to a record low of only USD 18.6 billion in 2024, its lowest level in three decades. This decline has continued through 2025, with FDI dropping another 10.9% year-on-year in the first four months of the year. This sharp drop is due to having confidence undermined among overseas investors, brought on by the simultaneity of various factors like escalating geopolitical risks, regulatory transparency, and lingering doubts over the health of the domestic economy. This top-line drop, however, conceals an essential structural change.

While investment is contracting in legacy sectors like property and legacy manufacturing, FDI into China's high-tech industry has been surprisingly strong. From 2019 to 2023, utilized FDI across high-tech sectors rose at a whopping average annual rate of 15% and accounted for 37% of the overall inflow. This reflects that while most businesses "de-risk" supply chains, China remains a destination of choice for investment in frontier segments like biopharma, new energy, and R&D, where its size of market and manufacturing value chain is unmatched.

Recent Developments and Geopolitical Factors

The single most significant external factor affecting China's economic fortunes is increasing strategic rivalry with the United States. After the 2024 U.S. election, trade tensions escalated spectacularly. Early in 2025, Washington imposed a series of heavy new tariffs on Chinese goods, prompting immediate tit-for-tat retaliation from Beijing in a vicious cycle of spiraling protectionism. This "tariff war" explicitly and existentially threatens China's export-driven growth model and is creating deep uncertainty for the world's supply chains. This trade war is closely linked with a contentious "tech war." The U.S. has imposed severe export controls on advanced semiconductors, chip-making equipment, and artificial intelligence technology, specifically in order to impede China's technological progress in strategic areas.

China has responded with its own export controls on key raw materials used to make semiconductors, such as gallium and germanium. Other high-risk geopolitical flashpoints, including tensions in the Taiwan Strait and China's "no-limits" partnership with Russia, contribute to compounding complexity, increasing the risk of miscalculation and conflict. This increasing competition is inducing a fundamental, and potentially excruciating, reorganization of the Chinese economy. The extraterritorial coercion of U.S. tariffs and technology embargoes is the principal cause of both the "de-risking" trend among Western firms and China's domestic motivation for "self-reliance." This has encouraged Beijing to double down on its state-led industrial policy, dumping enormous subsidies into building up indigenous capabilities in critical spaces like semiconductors, AI, and EVs.

As mentioned earlier, this investment drive by the government is causing humongous overcapacity, and that overcapacity then necessitates the export of the surplus. That flood of subsidized exports is becoming more and more seen in the West not merely as an economic threat but also as a national security threat, causing extra tariffs and quotas. The result is a vicious feedback loop in which China's brand of economics and geopolitics of confrontation have now become inextricably intertwined, driving the world's two largest economies further apart.

Key Corporate & E-Commerce Landscape |

This section identifies the leading corporate entities and dominant digital platforms that define China's modern economy. These companies are not only domestic giants but also major global players that serve as bellwethers for the country's economic health and technological ambitions.

Major Chinese Corporations

China's corporate landscape is dominated by a mix of state-owned behemoths in banking and energy, and private-sector technology titans that have achieved global scale. The following table lists the top 10 largest publicly traded Chinese companies by market capitalization as of March 2025, providing a snapshot of the most valuable sectors in the economy.

Rank | Company | Sector | Market Capitalization (USD Billion) |

1 | Tencent Holdings | Technology / Social Media / Gaming | 593.8 |

2 | Alibaba Group | E-commerce / Cloud Computing | 316.4 |

3 | ICBC (Industrial and Commercial Bank of China) | Banking / Financial Services | 313.6 |

4 | Kweichow Moutai | Consumer Goods / Beverages | 275.2 |

5 | Agricultural Bank of China | Banking / Financial Services | 245.2 |

6 | China Mobile | Telecommunications | 233.8 |

7 | China Construction Bank | Banking / Financial Services | 222.9 |

8 | Bank of China | Banking / Financial Services | 209.9 |

9 | PetroChina | Energy / Oil & Gas | 203.3 |

10 | Xiaomi | Consumer Electronics | 172.5 |

Leading E-Commerce Platforms

China's online shopping market is the largest and one of the most innovative in the world. It has expanded far beyond simple online buying into an intensively integrated social commerce, live stream, and entertainment-driven sales ecosystem. The market is highly concentrated in the hands of a few giants.

Taobao & Tmall (Alibaba Group): Together, the two platforms form the backbone of Chinese e-commerce with an estimated 45% market gross merchandise volume (GMV). Taobao is China's first C2C (consumer-to-consumer) marketplace, a gigantic virtual bazaar for small business operators and individual merchants. Tmall is its B2C (business-to-consumer) counterpart, the premier online mall for official brand flagship stores, domestic and international. It is Asia's largest B2C platform.

JD.com (Jingdong): A logistics and technology giant, JD.com is the second-largest retailer. Its single most important differentiator is its gigantic, proprietary network of logistics, which allows it to deliver incredibly fast and reliably, often within 24 hours. Although it started out as an electronics retailer, it has since grown to become a complete online mall for all consumer goods categories. Its strategic partnership with Tencent gives access to the massive user base of WeChat for marketing purposes as well as customer interaction.

Pinduoduo: The most disruptive Chinese e-commerce player over the last several years, Pinduoduo entered the record books with its hyper-growth. It was disrupted with a "social commerce" model, having users join groups in order to receive discounts. The group-buying strategy, coupled with a gamification user interface and deep penetration of lower-tier cities, allowed it to acquire an enormous base of price-sensitive consumers and quickly become a major threat to Alibaba and JD.com.

Douyin (TikTok): The social media giant, worldwide more commonly known as TikTok, has managed to transition successfully into a serious e-commerce player. By integrating shopping functions into its short video and live-streaming products seamlessly, Douyin has generated an immensely powerful new type of "interest-based" e-commerce. It is powered by creators, celebrities, and entertainment, turning the platform into a key driver of brand discovery and impulse buy, and reforming the retail landscape in the process.

Analyst's View & Outlook |

This chapter synthesizes the foregoing analysis to present a conclusive, forward-looking assessment of China's risk profile and investment outlook.

Synthesis of Findings

The research exhibits an economy with a striking gap between its headline performance and fundamental health. The government of China has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to achieve its politically set growth targets, successfully managing a transition from a collapsing real estate sector to a new high-technology manufacturing and export-led model. This has been achieved through a massive deployment of state resources, demonstrating the country's high degree of policy control and implementation efficiency.

Yet this state-directed expansion has been achieved at tremendous cost, creating and compounding agonizing structural risks. The strategy of employing debt-fueled investment and an export boom based on risk to balance long-term domestic consumption weakness is inherently unsustainable. The persistent property crisis and the sky-high, opaque liabilities of Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) represent a latent and systemic threat to the domestic financial system. Meanwhile, reliance on net exports as a principal growth driver is increasingly unsustainable in a global context of mounting trade aggressiveness and strategic competition. Persistent deflationary pressures and a battered labour market, particularly for the young, further undermine the very domestic demand that is required for a virtuous economic rebalancing.

Risk Assessment

The primary risks facing China are not of an imminent sovereign default on its low levels of external debt. Rather, the key risks are internal and structural:

Systemic Financial Risk: The potential for a domestic debt crisis originating in the property and LGFV sectors, which would necessitate a massive state-led bailout of the banking system, severely straining the sovereign's long-term fiscal capacity.

Stagnation and Deflation: The risk of a prolonged period of low-quality, debt-fueled growth, persistent deflation, and "Japan-style" stagnation, driven by weak domestic demand and a private sector focused on deleveraging rather than investment.

Geopolitical and Regulatory Risk: The high probability of continued escalation in the U.S.-China trade and technology war, which will disrupt supply chains, depress export growth, and deter foreign investment. This is compounded by high domestic regulatory uncertainty stemming from the opaque and centralized nature of the political system.

These risks are interconnected within a vicious cycle of cause and effect. Unstable domestic demand necessitates dependence on exports, generating trade friction. The friction creates a state-sponsored pursuit of self-sufficiency, producing overcapacity and additional export dumping, prompting additional protectionist retaliation.

Final Outlook |

Despite China's undeniable economic scale, production capacity, and greater inclination towards innovation, the confluence of negative factors currently prevails over the strengths. The nexus of severe internal imbalances (unhealthy consumption, excessive leverage), chronic property sector stagnation crisis, and rapidly accelerating external environment warns us towards a protracted period of heightened risk, low growth, and poor quality of growth.

The policy combination of the government, founded as it is on supply-side stimulus at the cost of heavy demand-side support, appears to be doubling down on a flawed model rather than addressing its root causes. Absent strong and convincing indications of a continued rebound in domestic demand, full resolution of the property and LGFV debt overhang, and significant easing of geopolitical tensions, the aggregate macro risk profile continues to be unfavorable.

While targeted, short-term opportunities do exist in specific industries complementary to state industrial policy (e.g., green tech, advanced manufacturing), a cautious to negative stance to the commitment of new, unhedged, long-term capital to the country is warranted. The danger of financial instability and regulatory uncertainty is great and is most likely to be medium-term enduring.

ABOUT | Prostancy |

| |

Prostancy is a consulting and execution firm that works all over the world and focuses on real estate, construction, trade, and strategic investment advice. We work closely with private investors, institutions, and corporate stakeholders to provide useful information and solutions that get results in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. We work at the crossroads of opportunity and execution, with a strong focus on high-impact projects and creating value. We can handle complicated situations and make things clear where others see uncertainty because we have a lot of market knowledge, experience in different fields, and a focus on accuracy. We don't just look at trends at Prostancy; we help make them happen. Our method is proactive, disciplined, and focused on the future. It encompasses everything from large-scale real estate projects to cross-border trade opportunities and capital strategies. We are proud of how quickly we can move, how long we can think, and how well we can get results that matter. Prostancy is your trusted partner in unlocking potential and securing strategic growth, whether you're looking into new markets or fine-tuning your investment strategy. Our goal is clear: to turn knowledge into power and chances into success. Visit www.prostancy.com or get in touch with our global advisory team for more information., |

For inquiries, contact us. |

Comments